Summary: New research using human brain organoids shows that early neural activity follows structured time-based patterns long before sensory experience begins. These findings suggest that the human brain comes preconfigured with a built-in “operating system” to organize information, rather than relying solely on external inputs to form its circuits.

The organoids produced complex activity signatures that resemble the brain’s default mode, suggesting a genetically encoded model for perception and cognition. The work opens the door to deeper insights into early brain development, neurodevelopmental disorders, and how toxins can affect the fetal brain.

Key facts:

Intrinsically patterned activity: The organoids produced organized neuronal activation patterns that resembled the brain’s default mode network despite no sensory input. Genetically encoded blueprint: Findings suggest that the brain begins to form circuits with built-in instructions before experience shapes them. Tool for understanding disorders: These early signatures can help identify developmental alterations related to diseases or toxic exposures.

Source: UC Santa Cruz

Human beings have long wondered when and how we begin to form thoughts. Are we born with a prewired brain or do thought patterns only begin to emerge in response to our sensory experiences of the world around us?

Now, science is getting closer to answering the questions that philosophers have pondered for centuries.

Researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz are using small models of human brain tissue, called organoids, to study the first moments of electrical activity in the brain.

A new study in Nature Neuroscience finds that early brain activations occur in structured patterns without any external experience, suggesting that the human brain is prewired with instructions on how to navigate and interact with the world.

“These cells clearly interact with each other and form circuits that self-assemble before we can experience anything from the outside world,” said Tal Sharf, assistant professor of biomolecular engineering in the Baskin School of Engineering and senior author of the study.

“There is an operating system that emerges in a primordial state. In my lab, we grow brain organoids to observe this primordial version of the brain’s operating system and study how the brain constructs itself before sensory experience shapes it.”

By improving our fundamental understanding of human brain development, these findings can help researchers better understand neurodevelopmental disorders and identify the impact of toxins such as pesticides and microplastics on the developing brain.

Studying the developing brain

The brain, similar to a computer, works with electrical signals – the activation of neurons. When these signals start firing and how the human brain develops are difficult topics for scientists to study, since the early developing human brain is protected inside the womb.

Organoids, which are 3D models of tissue grown from human stem cells in the laboratory, provide a unique window into brain development. The Braingeneers group at UC Santa Cruz, in collaboration with researchers at UC San Francisco and UC Santa Barbara, are pioneering methods for growing these models and taking measurements from them to gain insights into brain development and disorders.

Organoids are particularly useful for understanding whether the brain develops in response to sensory information (since they exist in the laboratory and not in the body) and can be ethically grown in large quantities.

In this study, researchers prompted stem cells to form brain tissue and then measured their electrical activity using specialized microchips, similar to those that run a computer. Sharf’s background in applied physics, computing, and neurobiology informs his expertise in modeling early brain circuitry.

“An organoid system that is intrinsically uncoupled from any sensory information or communication with the organs offers a window into what is happening with this self-assembly process,” Sharf said.

“That self-assembly process is really difficult to do with traditional 2D cell culture: you can’t get cellular diversity and architecture. Cells need to be in intimate contact with each other. We’re trying to control the initial conditions, so we can let biology do its wonderful work.”

Pattern production

The researchers observed the electrical activity of brain tissue as it self-assembled from stem cells into a tissue that can translate the senses and produce language and conscious thought.

They discovered that during the first months of development, long before the human brain is capable of receiving and processing complex external sensory information such as vision and hearing, its cells spontaneously began to emit electrical signals characteristic of the patterns underlying sensory translation.

Through decades of neuroscience research, the community has discovered that neurons fire in patterns that are not simply random. Instead, the brain has a “default mode”: a basic underlying structure for activating neurons that then becomes more specific as the brain processes unique signals like a smell or taste. This background mode describes the possible range of sensory responses that the body and brain can produce.

In their observations of individual neuron spikes in self-assembled organoid models, Sharf and his colleagues found that these early observable patterns bear a striking similarity to the brain’s default mode.

Even without having received any sensory input, they are activating a complex repertoire of time-based patterns or sequences, which have the potential to be refined for specific senses, hinting at a genetically encoded blueprint inherent to the neural architecture of the living brain.

“These intrinsically self-organizing systems could serve as a basis for building a representation of the world around us,” Sharf said.

“The fact that we can see them in these early stages suggests that evolution has discovered a way for the central nervous system to construct a map that would allow us to navigate and interact with the world.”

Knowing that these organoids produce the basic structure of the living brain opens a range of possibilities to better understand human neurodevelopment, diseases, and the effects of toxins on the brain.

“We are showing that there is a basis for capturing complex dynamics that could likely be signals of pathological onsets that we could study in human tissue,” Sharf said. “That would allow us to develop therapies, working with clinicians at a preclinical level to potentially develop compounds, drug therapies and gene editing tools that could be cheaper, more efficient and higher performing.”

Researchers from UC Santa Barbara, Washington University in St. Louis, Johns Hopkins University, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, and ETH Zurich participated in this study.

Key questions answered:

A: They show structured electrical patterns that emerge before any sensory input.

A: Yes, organoids self-assemble into networks that fire in coordinated patterns.

A: These early intrinsic patterns can shape the way the brain builds systems for feeling, learning, and thinking.

Editorial notes:

This article was edited by a Neuroscience News editor. Magazine article reviewed in its entirety. Additional context added by our staff.

About this neurodevelopment research news

Author: Emily Cerf

Source: UC Santa Cruz

Contact: Emily Cerf – UC Santa Cruz

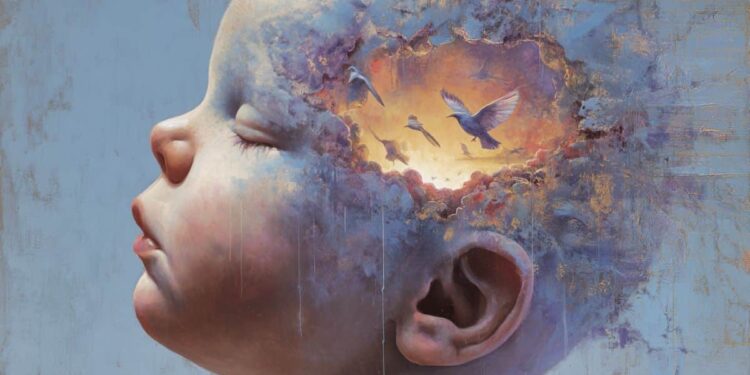

Image: Image is credited to Neuroscience News.

Original Research: Closed access.

“Preconfigured neuronal activation sequences in human brain organoids” by Tal Sharf et al. Nature Neuroscience

Abstract

Preconfigured neuronal activation sequences in human brain organoids

Neuronal firing sequences are believed to be the building blocks of information and transmission within the brain. However, it is still unclear when these sequences arise during neurological development.

Here we demonstrate that structured firing sequences appear in the spontaneous activity of human and murine brain organoids, both unguided and directed by forebrain identity, as well as ex vivo neonatal murine cortical slices.

We observed temporally rigid and flexible activation patterns in human and murine brain organoids and early postnatal murine somatosensory cortex, but not in dissociated primary cortical cultures.

These results suggest that temporal sequences do not arise in an experience-dependent manner, but rather are constrained by a preconfigured architecture established during neurodevelopment.

By demonstrating developmental recapitulation of neuronal activation patterns, these findings highlight the potential of brain organoids as a model for neuronal circuit assembly.