Summary: fMRI signals do not always match true brain activity levels, overturning a fundamental assumption used in tens of thousands of studies. In about 40% of cases, increased fMRI signal appeared in regions where neuronal activity was actually reduced, while decreased signals sometimes appeared in areas with increased activity.

By measuring actual oxygen use along with fMRI, scientists found that many brain regions increase their efficiency by extracting more oxygen rather than increasing blood flow. These findings raise important questions about how brain disorders have been interpreted and suggest that in the future imaging may need to shift toward direct measurements of energy consumption.

Key facts:

Mismatch revealed: In about 40% of cases, higher fMRI signals were related to lower neural activity. Change in oxygen efficiency: Brain regions often meet the demand for additional energy by extracting more oxygen rather than increasing blood flow. Clinical Impact: fMRI findings in depression, Alzheimer’s, and aging may reflect vascular differences rather than true changes in neuronal activation.

Source: TUM

Researchers from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU) found that an increased fMRI signal is associated with reduced brain activity in around 40 percent of cases. At the same time, they observed a decrease in fMRI signals in regions with elevated activity.

First author Dr. Samira Epp emphasizes: “This contradicts the long-standing assumption that increased brain activity is always accompanied by increased blood flow to meet increased oxygen demand. Since tens of thousands of fMRI studies worldwide are based on this assumption, our results could lead to opposite interpretations in many of them.”

Test tasks reveal deviations from standard interpretation

PD Dr. Valentin Riedl, now a professor at FAU, and his colleague Epp examined more than 40 healthy participants during their stay at TUM. Each was assigned several experimental tasks, such as mental arithmetic or retrieval of autobiographical memories, which are known to produce predictable fMRI signal changes in distributed brain regions. During these experiments, the researchers simultaneously measured actual oxygen consumption using a novel quantitative MRI technique.

Depending on the task and brain region, physiological results varied. The increase in oxygen consumption, for example in stone-related areas, did not coincide with the expected increase in blood flow.

Instead, quantitative analyzes showed that these regions met their additional energy demand by extracting more oxygen from the unchanged blood supply. Thus, they used the oxygen available in the blood more efficiently without requiring greater perfusion.

Implications for the interpretation of brain disorders.

According to Riedl, this knowledge also influences the interpretation of research results on brain disorders: “Many fMRI studies on psychiatric or neurological diseases, from depression to Alzheimer’s, interpret changes in blood flow as a reliable signal of insufficient or excessive activation of neurons. Given the limited validity of such measurements, this now needs to be re-evaluated.”

“Especially in patient groups with vascular changes, for example due to aging or vascular diseases, the measured values may mainly reflect vascular differences rather than neuronal deficits.” Previous studies in animals already point in this direction.

The researchers therefore propose to complement the conventional MRI approach with quantitative measurements. In the long term, this combination could form the basis for energy-based brain models: instead of showing activation maps that depend on assumptions about blood flow, future analyzes could show values that indicate how much oxygen – and therefore energy – is actually consumed for information processing.

This opens new perspectives to examine aging, psychiatric or neurodegenerative diseases in terms of absolute changes in energy metabolism and understand them more precisely.

Funding: The research was carried out at the Neuro-Head Center of the Institute of Neuroradiology of the TUM University Hospital. It was funded by the European Research Council through an ERC Starting Grant.

Key questions answered:

A: Because fMRI is based on changes in blood flow, not direct oxygen consumption, leading to misleading results when regions extract more oxygen from existing blood rather than increasing perfusion.

A: They combined fMRI with a quantitative MRI technique that directly tracked oxygen consumption, revealing discrepancies with standard assumptions based on blood flow.

A: Many previous studies may need reinterpretation, especially in groups with aging or vascular disease, where changes in blood flow may not reflect neuronal function.

Editorial notes:

This article was edited by a Neuroscience News editor. Magazine article reviewed in its entirety. Additional context added by our staff.

About this research news in neuroimaging and neurotechnology

Author: Ulrich Meyer

Source: TUM

Contact: Ulrich Meyer – TUM

Image: Image is credited to Neuroscience News.

Original research: Open access.

“BOLD signal changes can oppose oxygen metabolism in the human cortex” by Valentin Riedl et al. Nature Neuroscience

Abstract

BOLD signal changes may oppose oxygen metabolism in human cortex

fMRI measures brain activity indirectly by tracking changes in blood oxygenation levels, known as blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal, rather than directly measuring neural activity.

This approach is fundamentally based on neurovascular coupling, the mechanism that links neuronal activity with changes in cerebral blood flow. However, it is still unclear whether this relationship is consistent for positive and negative BOLD responses across the human cortex.

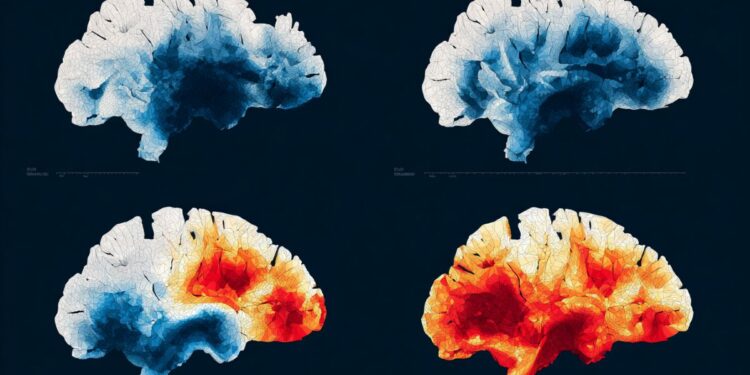

Here we found that about 40% of voxels with significant changes in BOLD signal during various tasks showed reversed oxygen metabolism, particularly in the default mode network.

These “discordant” voxels differed in initial oxygen extraction fraction and regulated oxygen demand through changes in oxygen extraction fraction, while “concordant” voxels depended primarily on changes in cerebral blood flow.

Our findings challenge the canonical interpretation of the BOLD signal, indicating that quantitative fMRI provides a more reliable assessment of absolute and relative changes in neuronal activity.