Summary: Researchers have identified two specific proteins, gliodin and CNTNAP4, that act as a “handshake” mechanism that allows inhibitory lamp cells to precisely connect with excitatory pyramidal neurons. This connection is vital to maintain electrical balance in the brain. Disruptions in this process are linked to neurological disorders such as epilepsy, schizophrenia and autism.

Source: Ohio State University

The brain’s ability to process information depends on a delicate balance between neurons that send “go” signals and those that send “stop” signals. Now, researchers have discovered exactly how the “conductors” of this orchestra get to the podium.

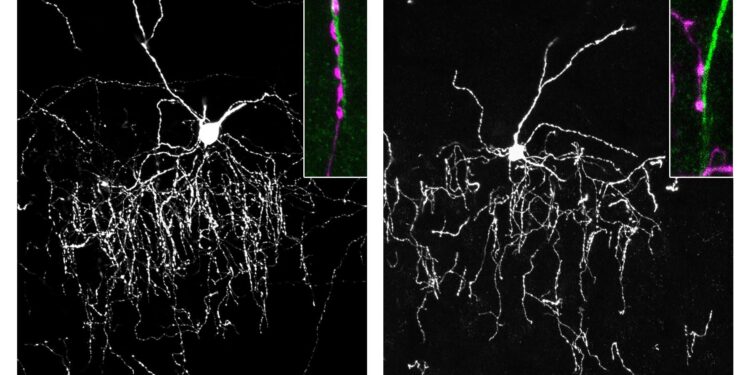

A new study from Ohio State University reveals how chandelier cells, a class of inhibitory interneurons, link to their target excitatory cells. The team identified two specific molecules that must be present to enable a “handshake” between cells, allowing synapses to form.

Chandelier cells are essential for brain function. They connect to a specific location on the target excitatory neurons (pyramidal cells) called the axon initial segment. By grasping this “handle,” spider-like cells can powerfully suppress the activity of excitatory neurons, effectively preventing uncontrolled electrical signals.

“These inhibitory interneurons shape and balance the activity of the local circuit: they are the modulators, coordinators and conductors of the orchestra,” said Yasufumi Hayano, lead author and postdoctoral scholar at The Ohio State University. “From our results, we have concluded that the interaction between two specific proteins regulates the specificity of their synapse formation.”

Loss of coordination between these cell types is associated with serious neurological and psychiatric disorders, such as epilepsy, depression, autism, and schizophrenia.

The molecular handshake

The researchers discovered that the connection is based on a precise molecular interaction. The study identified two key proteins:

CNTNAP4: Located in the chandelier cells (the “conductors”). Gliomedin: Located in the initial segment of the axon of target neurons.

When these two proteins meet, they facilitate the formation of the synapse. Using visualizations in the brains of young mice, the team observed that when the gliodin genes were deleted, the chandelier cells failed to form proper connections with their targets. The “handshake” broke down, leaving the “conductors” unable to control the orchestra.

Implications for neurological disorders

Because the initial segment of the axon is the exact site where neurons generate action potentials (the signals used to communicate), chandelier cells have a disproportionately strong influence on brain activity. They basically control the “tap” of the flow of information.

“This is basic neuroscience, but it could have an impact on neural disorders,” Hayano said. “If this process is disrupted, what happens? If we lose those genes, what neuronal disorder might occur? We don’t know yet, but those possibilities should be explored.”

Lead author Hiroki Taniguchi said understanding these developmental mechanisms is the first step toward identifying therapeutic targets for conditions in which brain circuits are imbalanced.

About this neuroscience research news

Author: Media Relations

Source: Ohio State University

Contact: Emily Caldwell – Ohio State University

Image: Image is credited to Ohio State University.

Original Research: Closed access.

“Highly localized interaction between Neurofascin-186 and Gliomedina promotes subcellular innervation by the chandelier cell” by Yasufumi Hayano et al. The journal of neuroscience

Abstract

The highly localized interaction between Neurofascin-186 and Gliomedin promotes subcellular innervation by the chandelier cell.

The brain’s ability to process information depends on a delicate balance between neurons that send “go” signals and those that send “stop” signals. Chandelier cells (ChCs) are a unique class of inhibitory interneurons that powerfully control the output of excitatory pyramidal neurons (PNs) by innervating their axon initial segments (AIS). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this precise subcellular synapse specificity remain poorly understood. Here, we identify a specific “handshake” mechanism between ChC and PN.

Using mice of both sexes, we demonstrate that neurofascin-186 (NF186), a cell adhesion molecule specifically expressed in the AIS of pyramidal neurons, is required for ChCs to develop a chain of synaptic boutons along the AIS. Furthermore, we found that gliomedin, a known receptor for NF186 at the nodes of Ranvier, is preferentially expressed in ChC and mediates ChC axon cartridge development by acting as a primary receptor for NF186.

Therefore, intercellular interaction through subcellularly restricted ligands and cell type-specific receptors ensures a high degree of specificity of the subcellular synapse of the inhibitory neuron. These findings support the concept that subcellular molecular tags recognized by interneuron subtype-specific receptors play a key role in establishing precise brain circuits.