![]()

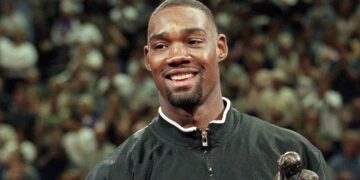

For more than a year, Diane Hunter, now 72, had experienced vague symptoms: pain in her spine and hips, nausea, exhaustion, thirst and frequent urination. His primary care doctor had ruled out diabetes before finally attributing his ailments to aging.

But months of intense back pain finally landed her in the emergency room, where a doctor suggested Hunter might have multiple myeloma. Hunter’s first question was, “What is that?”

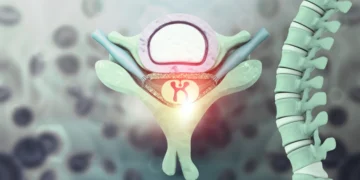

Multiple myeloma is a cancer that develops in the plasma cells of the bone marrow, displacing healthy blood cells and damaging bones. It is one of the most common blood cancers and the most diagnosed among African Americans. The mortality rate from multiple myeloma is also higher among African American patients than among white patients, and several studies show that, in addition to the biology of the disease, social factors such as socioeconomic status and lack of access to health insurance or medical services delay timely diagnoses.

A late diagnosis is what happened to Hunter, a black woman in Montgomery, Alabama. She said her primary care doctor overruled a recommendation from her endocrinologist to refer her to a hematologist after finding high levels of protein in her blood. Then, she said, he also refused to order a bone marrow biopsy after the ER doctor suggested he might have multiple myeloma. Fed up, she said, she found a new doctor, got tested and discovered she did indeed have the disease.

Monique Hartley-Brown, a multiple myeloma researcher at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, said Hunter’s experience is quite common, particularly among Black patients who live in underserved communities.

On average, patients visit their GP three times before receiving an accurate diagnosis. The delay from symptom onset to diagnosis is even longer for African Americans. “Meanwhile, the disease is wreaking havoc: causing fractures, severe anemia, fatigue, weight loss and kidney problems.”

Monique Hartley-Brown, multiple myeloma researcher, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Black and Hispanic patients are also less likely to receive newer therapies, according to the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation, and when they do, they are more likely to do so later in the course of their disease than white patients. An analysis published in 2022 of racial and ethnic disparities in multiple myeloma drug approval trials submitted to the FDA concluded that Black patients made up only 4% of participants despite being approximately 20% of those living with the disease.

Now, although significant progress has been made in understanding the biology of multiple myeloma and how to treat it, those racial gaps may widen amid federal cuts to cancer research and backlash against diversity and inclusion efforts. While few multiple myeloma experts were willing to speak on the record about the impact of the funding cuts, Michael Andreini, president and CEO of the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation, has written that cuts to the National Institutes of Health and its National Cancer Institute put future innovations at risk.

“Even before these potential cuts, myeloma funding lagged behind,” he wrote before the cuts were finalized. “The budget specifically for myeloma has decreased significantly. Myeloma accounts for nearly 2% of all cancers, but receives less than 1% of the NCI budget.”

The disease is already difficult to diagnose. Because multiple myeloma is typically diagnosed when a patient is over age 65 (African Americans tend to be diagnosed five years earlier, on average), common symptoms like low back pain and fatigue are often attributed to simply getting older.

That’s what happened to Jim Washington of Charlotte, North Carolina. He was 61 years old when excruciating hip pain suddenly stopped his regular tennis games.

“I thought he had done something to hurt me,” Washington said. “But I had played tennis all my life and this pain was unlike anything I had ever felt before.”

Washington was fortunate to have a concierge doctor and premium health insurance. In quick succession, he underwent x-rays that revealed a spinal injury and was referred to an oncologist, who identified a cancerous tumor. A subsequent biopsy and blood tests confirmed he had multiple myeloma.

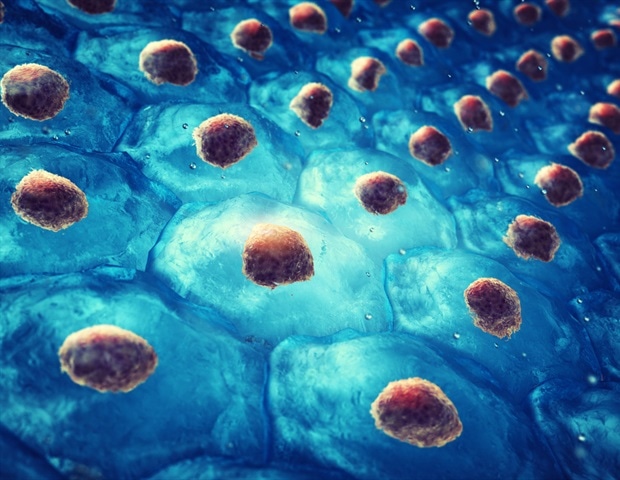

Washington underwent weeks of high-dose chemotherapy, followed by what is known as an autologous stem cell transplant, which used her own stem cells to regenerate healthy blood cells in her body. It was an exhausting process that ultimately left him in good health. Over the next few years, his doctors monitored him closely, including performing an annual bone marrow biopsy.

Before treatment, he said, myeloma had infiltrated 60% of his blood cells. The stem cell transplant reduced those levels to zero. However, after about five years, his multiple myeloma level had risen back to 10% and required more treatment.

But Washington had followed the latest research closely and believed he had reason to be optimistic. The FDA approved the first CAR T-cell therapy for multiple myeloma in 2021.

Hartley-Brown said the lack of black patients in multiple myeloma drug approval trials raises concerns about whether the trial results are equally applicable to the black population and may help explain why treatment advances have been less effective in black patients.

He cited multiple causes for the low trial participation rate, including historical distrust of the medical establishment and a lack of available clinical trials. “If you live in an underserved or underrepresented area, the community hospital or doctor may not have clinical trials available, or the patient may have limitations getting to that clinical trial-affiliated location,” he said.

Washington, a black patient, appears to have avoided this pitfall, having benefited from the latest treatments on both occasions. In January, he began six weeks of chemotherapy with a three-drug combination: Velcade, Darzalex and dexamethasone before undergoing CAR T-cell therapy.

To do this, doctors collected Washington T cells, a type of white blood cell, and genetically modified them to better recognize and destroy cancer cells before reinfusing them into his body. He did not require hospitalization after the transplant and was able to perform daily blood draws at home. His energy levels were much higher than during his first treatment.

“I’ve been in a very privileged position,” Washington said. “The prognosis is very positive and I feel good at the moment.”

Hunter also considers herself lucky despite receiving a late diagnosis. After her diagnosis in January 2017, she underwent five months of immunotherapy with a three-drug combination (Revlimid, Velcade and dexamethasone), followed by a successful stem cell transplant and two weeks of hospitalization. He has been in remission since July 2017.

Hunter, now a support group co-leader and patient advocate, said stories like Washington’s and hers provide hope despite cuts to research.

In the eight years since his treatment, he said, he has seen the thinking around multiple myeloma, long described as a treatable but incurable disease, begin to change as a growing subset of patients remain free of the disease for many years. He said he has even met people who have been living with the disease for 30 years.

“Now you’re hearing the word ‘cure,'” Hunter said.