Summary: Researchers mapped the brain connectivity of 960 people to discover how fast and slow neural processes come together to support complex behavior. They found that intrinsic neural timescales (each region’s characteristic window for processing information) are directly determined by white matter pathways that distribute signals throughout the brain. Individuals with a greater correspondence between their wiring and the demands of the regional time scale showed more efficient transitions between behaviorally linked brain states.

These fast-slow integration patterns were also linked to genetic and molecular characteristics and were conserved in mouse data, substantiating the findings in fundamental neurobiology. The results reveal a mechanistic link between brain architecture, information processing speed and cognitive ability.

Key facts

Intrinsic time scales: Each brain region processes information through its own characteristic window, from rapid sensory updates to slow integrative signals. Connectivity integration: White matter pathways link these regions, allowing fast and slow processes to converge into coherent behavior. Individual differences: People whose wiring better supports communication across time scales show stronger cognitive performance.

Source: Rutgers University

The human brain is constantly processing information that unfolds at different speeds, from split-second reactions to sudden environmental changes to slower, more reflective processes such as understanding context or meaning.

A new study from Rutgers Health, published in Nature Communications, sheds light on how the brain integrates these fast and slow signals across its complex network of white matter connectivity pathways to support cognition and behavior.

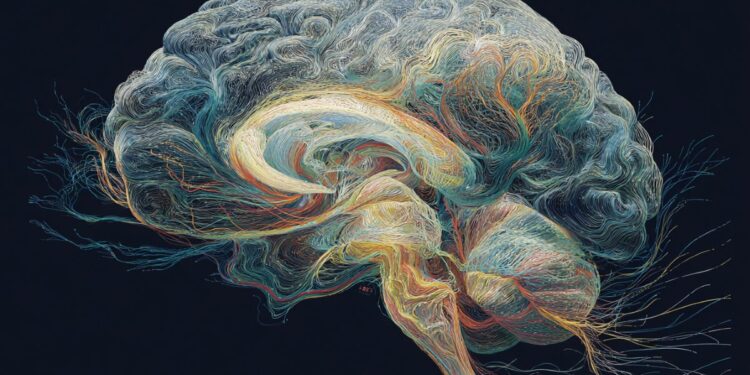

Different regions of the brain are specialized for processing information in specific time windows, a property known as intrinsic neural time scales, or INT for short.

“To affect our environment through action, our brain must combine information processed on different time scales,” said Linden Parkes, assistant professor of Psychiatry at Rutgers Health and senior author of the study.

“The brain achieves this by harnessing the connectivity of its white matter to share information between regions, and this integration is crucial for human behavior.”

To investigate how this integration works, Parkes and his team analyzed multimodal brain imaging data from 960 people. They built detailed maps of each person’s brain connectivity, known as connectomes, and applied mathematical models that describe how complex systems change over time to understand how information flows through these networks.

“Our work investigates the mechanisms underlying this process in humans by directly modeling the INT regions from their connectivity,” said Parkes, a senior member of the Rutgers Brain Health Institute and the Center for Advanced Human Brain Imaging Research.

“This establishes a direct link between how brain regions process information locally and how that processing is shared across the brain to produce behavior.”

The Rutgers researchers found that the distribution of neuronal time scales across the cortex plays a crucial role in how efficiently the brain switches between large-scale activity patterns related to behavior. It is important to note that this organization varies according to individuals.

“We found that differences in how the brain processes information at different speeds help explain why people vary in their cognitive abilities,” Parkes said.

The researchers also discovered that these patterns are related to genetic, molecular and cellular characteristics of brain regions, underpinning the findings in fundamental neurobiology. Similar relationships were observed in the mouse brain, suggesting that the mechanisms are conserved across species.

“Our work highlights a fundamental link between the brain’s white matter connectivity and its local computational properties,” Parkes said. “People whose brain wiring is better suited to how different regions handle fast and slow information tend to show greater cognitive ability.”

Building on these findings, the team is now expanding the work to study neuropsychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression, examining how disruptions in brain connectivity can alter information processing.

The study was conducted in collaboration with Avram Holmes, associate professor of psychiatry and senior member of the Rutgers Brain Health Institute and the Center for Advanced Human Brain Imaging Research, along with postdoctoral researchers Ahmad Beyh and Amber Howell, as well as Jason Z. Kim of Cornell University.

Key questions answered:

A: Different regions operate on intrinsic neural time scales, handling fast or slow information depending on their specialization.

A: People whose white matter wiring aligns well with these fast-slow processing demands show more efficient brain state switching and greater cognitive performance.

A: Disruptions in connectivity or timescale organization can alter the flow of information, offering a target for understanding conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression.

Editorial notes:

This article was edited by a Neuroscience News editor. Magazine article reviewed in its entirety. Additional context added by our staff.

About this research news in neuroscience and cognition

Author: Tongyue Zhang

Source: Rutgers University

Contact: Tongyue Zhang – Rutgers University

Image: Image is credited to Neuroscience News.

Original research: Open access.

“Inferring intrinsic neural time scales using optimal control theory” by Linden Parkes et al. Nature Communications

Abstract

Inferring intrinsic neural time scales using optimal control theory

The temporal evolution of whole-brain activity depends on complex interactions within and between brain regions that are mediated by neurobiology and connectivity, respectively.

Here, we provide a framework for studying these relationships that uses network control theory (NCT) to estimate the intrinsic neural timescales (INT) of regions.

Our approach expands the range of dynamics supported by the connectome and improves the alignment between the brain’s connectivity and its path through state space.

We found that our model-based INTs correlate with empirically measured INTs from functional neuroimaging data, neurobiological measures of gene expression and cell type densities, as well as measures of cognition.

We demonstrate consistent results across multiple data sets and species.

Finally, we show that our model-based INTs enable efficient control of brain states from fewer brain regions.

Our results provide a flexible quantitative framework that more accurately captures the interplay between brain structure, function, and intrinsic dynamics with greater biophysical realism.