Summary: A biologically based computational model built to mimic real neural circuits, not trained on animal data, learned a visual categorization task just as real laboratory animals do, comparing their accuracy, variability, and underlying neural rhythms. By integrating fine-scale synaptic rules with large-scale architecture in the cortex, striatum, brainstem, and acetylcholine-modulated systems, the model reproduced distinctive patterns of learning, including strengthened beta-band synchrony between regions during correct decisions.

It also revealed a set of “incongruent neurons” that predicted errors, a signal that the researchers only recognized in their animal data after the model exposed it. This biomimetic platform provides a powerful model to explore disease-related circuit changes and test therapeutic interventions in silico, offering a new avenue to develop next-generation neurotherapeutics.

Key facts

Biology-first design: The model incorporates real-world neural connectivity rules, neurotransmitter dynamics, and multi-region architecture to replicate biological computing. Emergent realism: Produced learning behavior, beta synchrony, and decision patterns that matched laboratory animals, even without being trained on biological data sets. Hidden signals exposed: Discovery of “incongruent neurons” reveals overlooked error-predictive activity in real brains.

Source: MIT Picower Institute

A new computational model of the brain based closely on its biology and physiology not only learned a simple visual category learning task exactly as well as lab animals, but even enabled the discovery of counterintuitive activity by a group of neurons that researchers working with animals to perform the same task had not noticed in their data before, said a team of scientists from Dartmouth College, MIT, and the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

Notably, the model produced these achievements without even being trained with data from animal experiments. Instead, it was built from the ground up to faithfully represent how neurons connect into circuits and then communicate electrically and chemically across broader brain regions to produce cognition and behavior.

Then, when the research team asked the model to perform the same task they had previously performed with the animals (looking at patterns of dots and deciding which of two broader categories they fit), it produced very similar neural activity and behavioral results, acquiring the skill with almost exactly the same erratic progress.

“It’s simply producing new simulated graphs of brain activity that are only then compared to lab animals. The fact that they match as strikingly as they do is quite shocking,” said Richard Granger, professor of psychology and brain sciences at Dartmouth and lead author of a new study in Nature Communications describing the model.

One goal in creating the model, and the new iterations developed since the paper was written, is not only to offer insights into how the brain works, but also how it might function differently in diseases and what interventions might correct those aberrations, added co-author Earl K. Miller, the Picower Professor at MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory.

Miller, Granger and other members of the research team founded the company Neuroblox.ai to develop biotechnological applications of the models. Co-author Lilianne R. Mujica-Parodi, a professor of biomedical engineering at Stony Brook and lead principal investigator of the Neuroblox Project, is the company’s CEO.

“The idea is to create a platform for biomimetic modeling of the brain so that you can have a more efficient way to discover, develop and improve neurotherapy. Drug development and efficacy testing, for example, can occur earlier in the process, on our platform, before the risk and expense of clinical trials.” said Miller, who is also a faculty member in MIT’s Brain and Cognitive Sciences department.

Making a biomimetic model

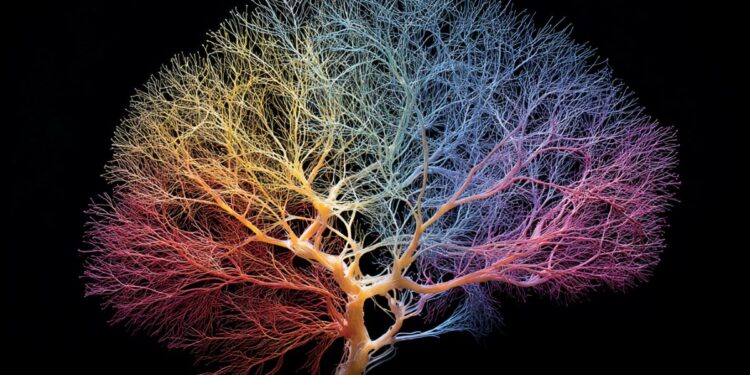

Dartmouth postdoc Anand Pathak created the model, which differs from many others in that it incorporates small details, such as how individual pairs of neurons connect to each other, and large-scale architecture, including how information processing between regions is affected by neuromodulatory chemicals such as acetylcholine.

Pathak and the team iterated on their designs to make sure they obeyed several limitations seen in real brains, such as the way neurons synchronize using broader rhythms. Many other models focus only on small or large scales, but not both, he said.

“We didn’t want to lose the tree and we didn’t want to lose the forest,” Pathak said.

The metaphorical “trees,” called “primitives” in the study, are small circuits of a few neurons each that connect based on electrical and chemical principles of real cells to perform fundamental computational functions.

For example, within the version of the cerebral cortex model, a primitive design has excitatory neurons that receive information from the visual system through synaptic connections affected by the neurotransmitter glutamate.

Those excitatory neurons then connect densely with inhibitory neurons in a competition to tell them to turn off other excitatory neurons—a winner-take-all architecture found in real brains that regulates information processing.

On a larger scale, the model encompasses four brain regions necessary for basic learning and memory tasks: a cortex, a brainstem, a striatum, and a “tonically active neuron” (TAN) structure that can inject some “noise” into the system through bursts of acetylcholine.

For example, when the model was engaged in the task of categorizing the presented dot patterns, the TAN at first ensured some variability in the way the model acted on the visual input so that the model could learn by exploring various actions and their outcomes.

As the model continued to learn, circuits in the cortex and striatum strengthened connections that suppressed TAN, allowing the model to act on what it was learning more consistently.

As the model engaged in the learning task, real-world properties emerged, including a dynamic that Miller has commonly observed in his animal research. As learning progressed, the cortex and striatum became more synchronized in the “beta” frequency band of brain rhythms, and this greater synchrony correlated with the times when the model (and the animals) made the correct categorical judgment about what they were seeing.

Revealing ‘incongruent’ neurons

But the model also presented the researchers with a group of neurons (about 20 percent) whose activity seemed highly predictive of error. When these so-called “incongruent” neurons influenced the circuits, the model made the wrong category judgment. At first, Granger said, the team thought it was a quirk of the model. But then they looked at real brain data that Miller’s lab accumulated when animals performed the same task.

“Only then did we go back to the data we already had, certain that this couldn’t be there because someone would have said something about it, but it was there and it had never been noticed or analyzed,” he said.

Miller said these counterintuitive cells might have a purpose: It’s all very well learning the rules of a task, but what if the rules change? Trying alternatives from time to time can allow the brain to encounter a new set of emerging conditions. In fact, a separate Picower Institute lab recently published evidence that humans and other animals sometimes do this.

While the model described in the new paper exceeded the team’s expectations, Granger said, the team has been expanding it to make it sophisticated enough to handle a greater variety of tasks and circumstances. For example, they have added more regions and new neuromodulatory chemicals. They have also begun to test how interventions such as drugs affect their dynamics.

In addition to Granger, Miller, Pathak, and Mujica-Parodi, the paper’s other authors are Scott Brincat, Haris Organtzidis, Helmut Strey, and Evan Antzoulatos.

Funding: Research support was provided by the Baszucki Brain Research Fund, United States, Office of Naval Research, and Freedom Together Foundation.

Key questions answered:

A: It learned the visual category task with almost identical patterns of progress, neural activity, and learning dynamics, even without training with biological data.

A: It revealed a population of “incongruent neurons” that predicted errors. When researchers checked old animal data, the same pattern was present but had gone unnoticed.

A: It provides a platform to probe brain computing, simulate disease states, and test neurotherapeutics before moving on to costly and risky trials.

Editorial notes:

This article was edited by a Neuroscience News editor. Magazine article reviewed in its entirety. Additional context added by our staff.

About this news on AI research, learning and neuroscience

Author: David Orenstein

Source: MIT Picower Institute

Contact: David Orenstein – MIT Picower Institute

Image: Image is credited to Neuroscience News.

Original research: Open access.

“Biomimetic model of corticostriatal microassemblies uncovers a neural code” by Richard Granger et al. Nature Communications

Abstract

A biomimetic model of corticostriatal microarrays uncovers a neural code

Although computational models have deepened our understanding of neuroscience, it remains a major challenge to link actual low-level physiological activity (spikes, field potentials) and biochemistry (transmitters and receptors) directly to high-level cognitive abilities (decision making, working memory) and associated disorders.

Here, we present a mechanically accurate multiscale model that directly generates a simulated physiology from which extended neural and cognitive phenomena emerge.

The model produces spikes, fields, phase synchronies and synaptic changes, directly generating working memory, decisions and categorization.

These were then validated with extensive experimental data from macaques from which the model received no pre-training of any kind. Furthermore, the simulation uncovered a previously unknown neural code (“incongruent neurons”) that specifically predicts future erroneous behaviors, which were also subsequently confirmed with empirical data.

In this way, the biomimetic model directly and predictively links decision and reinforcement signals, of computational interest, with field and activation codes, of neurobiological importance.