Sudden dizziness when standing up It can be alarming, especially when it happens out of nowhere or reappears again and again. Many people wonder if this could be a sign of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) or simply low blood pressure.

What is POTS?

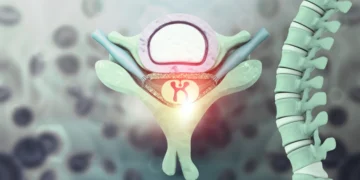

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is an autonomic nervous system disorder that affects the way the body regulates heart rate and blood flow when a person goes from lying or sitting to standing. It is characterized by an abnormally large increase in heart rate when standing, often accompanied by symptoms such as dizziness, lightheadedness, and fatigue.

In POTS, blood can pool in the lower body when someone stands up, forcing the heart to beat faster in an attempt to maintain blood flow to the brain. This can make a person feel weak, unsteady, or as if their vision is blurry, especially after standing for several minutes. POTS is more common in younger people and those assigned female at birth, but it can affect anyone.

How POTS affects the body

When a healthy person stands up, the body quickly constricts blood vessels and slightly increases heart rate to keep blood flowing upward against gravity, according to the study. American Heart Association. In POTS, this adjustment is affected, so the heart rate increases much more than normal, while blood pressure often stays the same or fluctuates rather than decreasing dramatically. This abnormal response can make standing or even sitting upright tiring or uncomfortable.

Because the autonomic nervous system is involved in many bodily functions, POTS can cause a wide range of symptoms in addition to dizziness when standing. People may experience brain fog, nausea, tremors, palpitations, and exercise intolerance, making it difficult to manage daily activities, school, or work over time.

Common POTS Symptoms to Look Out For

Typical POTS symptoms They are often grouped together rather than appearing in isolation. Common features include:

Dizziness or lightheadedness after standing for a few minutes. Palpitations or palpitations noticeable when standing. Generalized fatigue or feeling “exhausted” after relatively small activities.

Additionally, many people with POTS report symptoms such as brain fog, difficulty concentrating, headaches, nausea, difficulty breathing, chest discomfort, shaking, or a feeling of internal “adrenaline.” Some people notice that symptoms worsen with heat, prolonged standing, with menstruation or after viral illnesses, and improve when lying down.

How long does dizziness last with POTS?

With POTS, dizziness when standing often begins shortly after standing and may persist as long as the person remains in that position, especially if standing. Symptoms often improve when the person sits or lies down, as the effect of gravity on blood pooling is reduced.

Because symptoms can vary from day to day, many people benefit from keeping a brief symptom diary. Noting when dizziness occurs, how long it lasts, what position you were in, and whether you experienced other POTS symptoms can help doctors see patterns over time.

Low blood pressure and dizziness.

Orthostatic or postural hypotension specifically refers to a significant drop in blood pressure when a person stands up. This drop in pressure can reduce blood flow to the brain, causing dizziness, blurred or tunnel vision, weakness, or fainting. Older adults, people taking blood pressure medications or diuretics, and those who are dehydrated are particularly vulnerable.

When low blood pressure is the primary problem, heart rate may increase slightly to compensate, but not to the same degree as typically seen in POTS. Measuring blood pressure and heart rate while lying down and again after standing can help distinguish between these patterns, although formal testing should be guided by a healthcare provider, according to Mayo Clinic.

Can POTS cause low blood pressure?

POTS is primarily defined by changes in heart rate rather than a specific pattern of blood pressure, but some people experience low or fluctuating blood pressure along with their POTS symptoms. In these cases, both tachycardia and low blood pressure can contribute to dizziness when standing up, making the symptoms feel more intense.

Others may have normal or even slightly elevated blood pressure while still meeting the criteria for POTS. This is why focusing solely on the term “low blood pressure” can sometimes be misleading and why professional evaluation is essential when symptoms are frequent, severe, or worsening.

Why do people get dizzy when standing?

From a physiological perspective, standing draws blood to the legs and lower body. The body must quickly constrict blood vessels and adjust heart rate to maintain sufficient blood flow to the brain and vital organs. If this response is delayed, insufficient, or incorrectly exaggerated, dizziness or lightheadedness may occur.

Simple triggers such as standing up suddenly after sitting for a long time, being in a hot shower, or not drinking enough fluids can cause brief dizziness in otherwise healthy people. When dizziness is persistent or accompanied by other POTS symptoms, low blood pressurechest pain or fainting, becomes more concerning and warrants evaluation.

Diagnosis and medical evaluation.

When dizziness upon standing is frequent or disabling, medical evaluation is important. Doctors usually begin with a detailed history of symptoms, a physical examination, and measurements of heart rate and blood pressure while lying, sitting, and standing. If POTS is suspected, some people undergo a standing or tilt-table test to document how heart rate and blood pressure change over time.

Blood tests, heart rhythm monitoring, or additional imaging may be ordered to rule out other causes, such as anemia, thyroid disorders, structural heart disease, or neurological conditions. A diagnosis of POTS is made when characteristic heart rate changes and symptom patterns are present, other important causes have been excluded, and symptoms have persisted for a significant period (often several months).

Living with chronic orthostatic symptoms

For those who are ultimately diagnosed with POTS or chronic orthostatic hypotension, the impact on daily life can be significant. Daily routines, work schedules, and exercise plans often need adjustments to account for varying energy levels and symptom flare-ups. Planning breaks, using stools or chairs when tasks involve prolonged standing, and pacing activities are common strategies.

Support for emotional and mental health is also important. Because POTS symptoms and dizziness upon standing are often invisible to others, people may feel misunderstood or dismissed. Education, support groups, and a validating medical team can make a substantial difference in long-term coping and quality of life.

Frequently asked questions

1. Can someone have POTS without feeling dizzy?

Yes. While dizziness upon standing is common in POTS, some people primarily notice extreme fatigue, brain fog, or palpitations rather than obvious lightheadedness. They may not relate these symptoms to postural changes until a doctor measures heart rate and blood pressure in different positions.

2. Does drinking more water always help dizziness when standing?

Increased fluid intake can reduce dizziness in many people with orthostatic problems, but it is not a panacea and may not be appropriate for everyone. People with heart, kidney or certain endocrine conditions need personalized advice, so any major changes in fluid or salt intake should be discussed with a healthcare professional.

3. Can POTS or orthostatic dizziness appear suddenly after an illness?

Yes. Some people report that POTS-like symptoms begin or worsen after viral infections, surgery, or periods of prolonged bed rest. In these cases, the autonomic nervous system may have been altered or deconditioned, and symptoms may evolve over weeks or months rather than appearing all at once.

4. Is it safe to exercise if you get dizzy while standing?

Many people with POTS or orthostatic dizziness can exercise safely, but the type and intensity often need to be modified. Doctors typically recommend starting with recumbent or semi-recumbent activities and then gradually progressing under medical guidance, rather than abruptly performing upright, high-intensity exercises that could worsen symptoms.