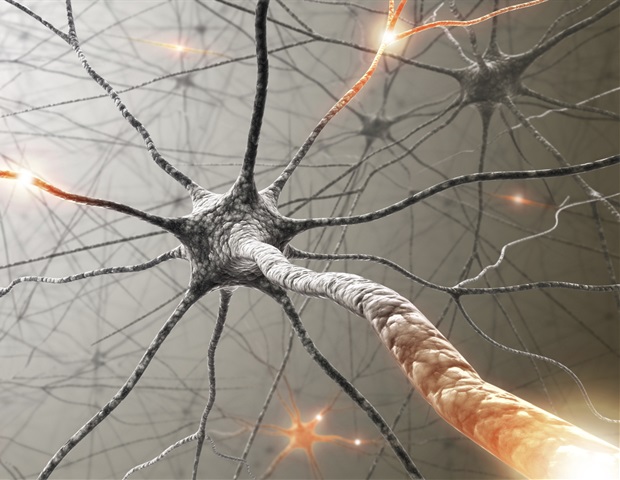

Scientists have discovered that messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules, which carry genetic instructions far into neurons in the brain, tend to cluster together, primarily because they are abundant, rather than because they travel in coordinated groups.

The findings, published in the journal eNeuro, help explain how neurons, which have the longest processes of any cell in the body, manage genetic instructions far from where they are generated.

This fundamental process is important for supporting neuronal communication and the modifications that occur at specific cellular communication sites called synapses along neurons, which are part of the cascade of molecular signals that occur during learning and memory formation.

When these processes break down, as occurs in conditions such as Fragile X syndrome and some forms of autism, understanding the basic rules that guide RNA localization could help scientists pinpoint where things are going wrong.

When we compared all possible pairs of measured mRNAs (66 combinations in total), the simplest explanation fit best. That is, abundant mRNAs are simply more likely to overlap in signal with other mRNAs measured. This refers to a flexible system in which mRNAs travel nearby by chance. The real specificity appears to occur later at the synapse, where local signals determine how the genetic instructions are used. ”

Shannon Farris, assistant professor at VTC Fralin Biomedical Research Institute and lead study author

Some scientists have proposed that these mRNAs travel in separate packets carrying specific combinations, while others have proposed that each message travels on its own. The new study leans toward the simpler idea that proximity depends primarily on the amount of each message a cell generates.

This insight not only provides a new perspective on basic biology, but also helps reveal how neurons manage messages that guide learning and memory, including processes that are disrupted in Fragile X syndrome, a genetic condition in which proteins that bind many of these RNAs are missing.

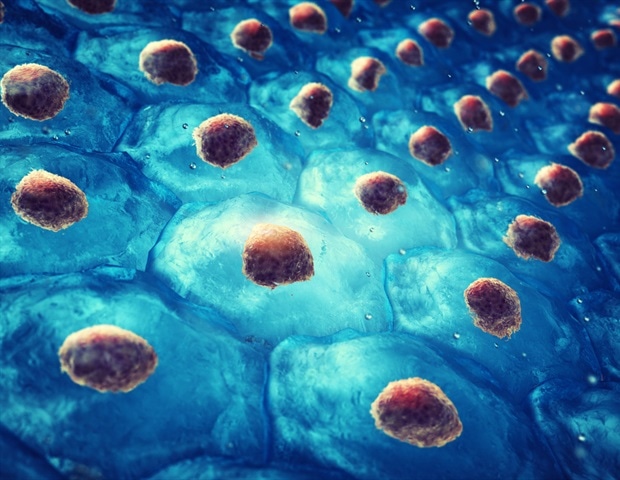

The researchers used single-molecule imaging in intact hippocampal tissue from wild-type mice to spatially map RNA messages. Many RNA messages are known to interact with a regulatory protein called FMRP. They measured the size and brightness of each glowing RNA dot and compared how often different RNAs appeared to overlap spatially.

Now that scientists have a clearer picture of how these molecules are arranged in nature, next steps include examining how this system adapts during learning and how it goes off track in diseases that affect communication between neurons, such as Fragile X syndrome.

The study was conducted by Faris, an assistant professor at the institute and in the Department of Biomedical and Pathobiology at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine. The lead author is Renesa Tarannum of the Virginia Tech Translational Biology, Medicine, and Health Graduate Program. Sharon Swanger, assistant professor in the Institute and Department of Biomedical and Pathobiology; Oswald Steward, director of the Reeve Irvine Spinal Cord Injury Research Center at the University of California, Irvine.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute of Mental Health, the Fralin Institute for Biomedical Research at Virginia Tech, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation.

sauce:

Reference magazines:

Tarannam, R., et al. (2025). Multiplexed smFISH revealed that the spatial organization of neuropil-localized mRNAs is related to abundance. e-neuro. doi: 10.1523/eneuro.0184-25.2025. https://www.eneuro.org/content/12/12/ENEURO.0184-25.2025