A new study by Pitt researchers defies an assumption of decades in neuroscience by showing that the brain uses different transmission sites, not a shared site, to achieve different types of plasticity. The findings, published in Science Advances, offer a deeper understanding of how the brain balances flexibility stability, an essential process for learning, memory and mental health.

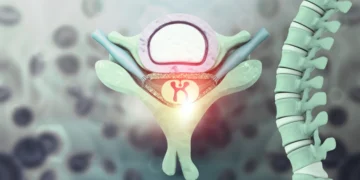

Neurons communicate through a process called synaptic transmission, where a neuron releases chemical messengers called neurotransmitters from a presynaptic terminal. These molecules travel through a microscopic gap called synaptic cleft and bind to receptors in a neighboring postsynaptic neuron, which triggers an answer.

Traditionally, scientists believed that spontaneous transmissions (signals that occur randomly) and evoked transmissions (signals triggered by entry or sensory experience) originated from a type of canonical synaptic site and were based on shared molecular machinery. Using a mouse model, the research team, led by Oliver Schlüter, associate professor of neuroscience at the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, discovered that the brain uses separate synaptic transmission sites to carry out a regulation of these two types of activity, each with its own timeline and regulatory rules.

We focus on the primary visual cortex, where cortical visual processing begins. We expected that spontaneous and evoked transmissions follow a similar development trajectory, but instead, we found that they diverged after the opening of the eyes. “

Yue Yang, research associate in the Department of Neuroscience and first author of the study

When the brain began to receive visual information, evoked transmissions continued to strengthen. On the contrary, spontaneous transmissions are stabilized, which suggests that the brain applies different forms of control to the two signaling modes.

To understand why, researchers applied a chemist that activates silent receptors on the postsynaptic side. This caused spontaneous activity to increase, while the evoked signals remained unchanged, strong evidence that the two types of transmission operate through functionally different synaptic sites.

It is likely that this division allows the brain to maintain a substantive activity consistent through spontaneous signage while refining the relevant behavior paths through evoked activity. This dual system admits both homeostasis and hebbian plasticity, the experience dependent on the experience that strengthens neuronal connections during learning.

“Our findings reveal a key organizational strategy in the brain,” said Yang. “By separating these two signaling modes, the brain can remain stable and remain flexible enough to adapt and learn.”

The implications could be wide. The abnormalities in synaptic signage have been related to conditions such as autism, Alzheimer’s disease and substance use disorders. A better understanding of how these systems operate in the healthy brain can help researchers identify how they are interrupted in the disease.

“Learning how the brain normally separates and regulates different types of signals brings us closer to understanding what could go wrong in neurological and psychiatric conditions,” Yang said.

Fountain:

Newspaper reference:

Yang, Y., et al. (2025). Different transmission sites within a synapse for strengthening and homeostasis. Scientific advances. doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ads5750.

(Tagstotransilate) brain