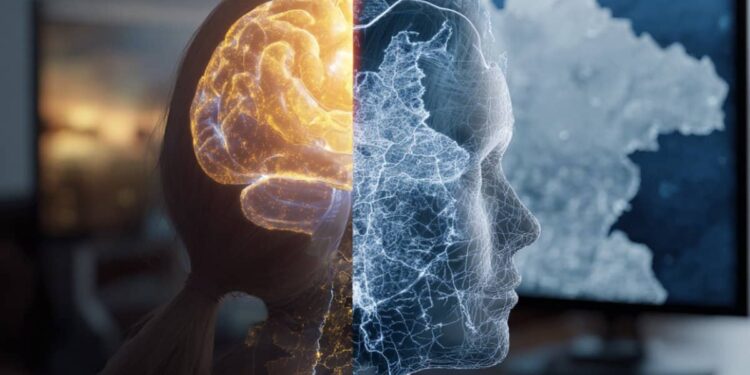

Summary: When you imagine a map in your mind, your brain uses different pathways than when you actually look at one. In a study on spatial attention, participants recalled a map of France and judged which city was closest to Paris.

Brain recordings revealed that visual attention depended on posterior regions of the brain, while mental imagery depended more on frontal areas. These results show that the brain separates the way it processes imagined and perceived spaces, activating different neural mechanisms for each.

Key facts:

Different neural pathways: Visual attention involves posterior regions of the brain, while mental imagery relies on frontal networks. Mind’s eye navigation: People can direct spatial attention within mental images just as they do when viewing real images. Duality of attention: imagining and perceiving space activate separate mechanisms, offering information about memory and consciousness.

Source: SfN

Spatial attention enhances the processing of specific regions within a visual scene when people view their environment, as if it were a spotlight. Do people orient spatial attention in the same way when processing mental images from memory?

Anthony Clément and Catherine Tallon-Baudry of the École normale supérieure explored whether the neural mechanisms of spatial attention differ when discriminating between locations in mental and visual images on a screen.

In their Journal of Neuroscience article, the researchers present an experimental task they developed that allowed them to record brain activity while human participants performed spatial discrimination tasks.

One task activated the “mind’s eye” by asking participants to remember the map of France and focus their attention on the right or left of their mental maps.

At the end of each trial, two city names appeared on a screen. Participants had to imagine where the cities were located on the map and choose which one they thought was closest to Paris.

People could orient spatial attention when retrieving images from memory, but the brain mechanisms were different compared to the mechanisms for discriminating between images on a screen.

While visual perception was based on the posterior regions of the brain, mental images were based more on the frontal areas. Therefore, there may be different mechanisms for spatial attention depending on whether people are imagining or viewing images.

Says Clément: “Our findings suggest that when we explore a mental image in our ‘mind’s eye,’ we are not simply reusing the brain mechanisms we rely on when we look at the world. This distinction can help us refine the way we think about internal experiences such as mental images, memory, thoughts, and even consciousness.”

About this neuroscience research news

Author: SfN Media

Source: SfN

Contact: SfN Media – SfN

Image: Image is credited to Neuroscience News.

Original Research: Closed access.

“Mental imagery in long-term memory differs from perception: evidence for distinct spatial formats and distinct mechanisms of orienting spatial attention” by Anthony Clément et al. Neuroscience Magazine

Abstract

Mental imagery in long-term memory differs from perception: Evidence for distinct spatial formats and distinct mechanisms of orienting spatial attention.

How is spatial attention deployed in mental images?

Mental imagery is often assumed to share mechanisms with visual perception and visual working memory. Endogenous top-down spatial attention, in both visual perception and working memory, modulates behavior and parieto-occipital alpha band activity.

However, working memory captures only a subset of mental images, which can also draw on long-term memory.

Here, we ask whether and how spatial attention operates on mental images derived from general knowledge in long-term memory, and whether it recruits the same neural mechanisms as visual perception.

We recorded EEG in 28 healthy volunteers (13 men, 15 women) while they performed two spatially cue discrimination tasks (70% validity): one involving mental visualization of a long-term memory map (a map of France) and the other using visual stimuli. We show that spatial attention shortens response times in both tasks, but through different mechanisms.

Behavioral attentional benefits were not correlated across tasks, and spatial attention to mental imagery involved distinct neural mechanisms, with modulation of frontal rather than posterior alpha activity. Furthermore, we reveal fundamental differences in the spatial structures of mental imagery and visual perception.

Taken together, our results show that mental images extracted from long-term semantic memory are spatially organized and amenable to the deployment of spatial attention, but the underlying neural mechanisms differ from those of visual perception.

Therefore, our results point to marked differences between mental images from long-term memory and visual perception.